LEGEND OF AL CAPONE IN BENLD, THOUGH DEBATED, STILL LINGERS

by Tom Emery

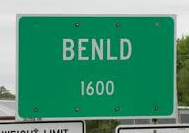

In a town the size of Benld (pop. 1,600), the phrase “urban legend” may be a misnomer. But rumors of gangster Al Capone in the town persist, nine decades later.

In a town the size of Benld (pop. 1,600), the phrase “urban legend” may be a misnomer. But rumors of gangster Al Capone in the town persist, nine decades later.

Though unproven, many residents of this southern Macoupin County village believe that Capone conducted all sorts of illegal business in Benld, including the manufacture of bootleg liquor.

A mining town established in 1904 with a high immigrant population, Benld (pronounced “beh-NELD”), 50 miles northeast of St. Louis, boasted 3,300 residents with at least 32 saloons around the start of Prohibition. It has since been described as a sort of “frontier town,” based on its lawless reputation.

Some including George Lacy, who grew up in Benld and now lives in Carlinville, firmly believe Capone in Benld on multiple occasions. “Everyone knew he was here,” said Lacy in an interview before his death in 2017. “He had a still that was camouflaged as a mine.”

Some including George Lacy, who grew up in Benld and now lives in Carlinville, firmly believe Capone in Benld on multiple occasions. “Everyone knew he was here,” said Lacy in an interview before his death in 2017. “He had a still that was camouflaged as a mine.”

Located in a secluded area on the east edge of Benld, the still was known as “No. 5 Mine” to the locals. Traces of the still are still visible today. “Capone would ship that liquor to Chicago,” said Lacy. “It seems like he was here quite a bit.”

**Editor’s Note: If you find the story here of value, consider clicking one of the Google ads embedded in the story. It costs you nothing but Google will give the website owner a few cents. This is a way to help support local news at no cost to the reader.

Lacy, who was known for his clear memory, was not alone in believing Capone was in Benld. Many other elderly residents through the years say they also saw Capone in town. Some believe that Capone stayed at a local boarding house, while others say that Capone was also involved in local prostitution.

A popular tale is that Capone frequented the Coliseum Ballroom, a local landmark that hosted countless big bands and pop-music acts and was destroyed by fire on July 31, 2011. The Coliseum was built in 1924 by members of the Tarro family, including Dominic, a grocer whose body was found floating in the Sangamon River near Springfield in 1930.

Lacy and others believe the murder resulted from a failed business deal with Capone. “Capone bought sugar from Tarro for his still, but Tarro got greedy,” said Lacy. “He held a few sacks of corn sugar back and sold them in his store, and Capone found out.”

Even today, some older residents still refuse to talk about Capone. “They were always afraid of what was going on, and still are,” said former Benld mayor Mickey Robinson. “They didn’t want to get involved.”

However, there is no mention of Benld in Capone’s leading biographies, and no proof exists that Capone was ever in the town. Capone was also in prison for ten months starting in May 1930 and again from 1932-39, reducing the window of time that he could have been in Benld.

“I’ve never come across anything indicating Capone was in Benld,” said Taylor Pensoneau of New Berlin, Ill., an acclaimed author who has extensively researched Prohibition-era gangsters in Illinois, particularly the notorious Shelton brothers.

**Editor’s Note: If you find the story here of value, consider clicking one of the Google ads embedded in the story. It costs you nothing but Google will give the website owner a few cents. This is a way to help support local news at no cost to the reader.

“Most of Illinois south of Peoria was Shelton gang territory during Prohibition,” continued Pensoneau. “Capone’s only appearances in downstate Illinois back then, to my knowledge, were to go duck hunting in places near the Illinois River like Havana and Beardstown.”

At times, Benld has tried to overlook its past reputation. A 1978 article stated that Benld was “trying to forget its wide-open past,” though many today embrace the Capone story, despite the lack of hard evidence. A tavern in downtown Benld is now named for Capone, and Robinson and a few others hope to establish a museum to Capone in Benld as a tourist attraction.

“There are only a few people left in town who would be old enough to remember Capone,” said Robinson. “A lot of younger residents today have no idea of Al Capone, and those that do are going off rumors.”

Lloyd Strohbeck of the Macoupin County Historical Society estimated before his death that “three-fourths of our members believe the story. A lot of it is just hearsay, though.”

The Capone legend reflects Americans’ seeming fascination with Prohibition-era gangsters. “Folks love to read about black sheep in society, and gangsters or outlaws have been glamorized in magazines, pulp fiction, and Hollywood films,” said Pensoneau. “I also think that some people – while not admitting it – have lived vicariously through the escapades and antics of gangsters.”

Tom Emery is a freelance writer and researcher from Carlinville. He may be reached at 217-710-8392 or ilcivilwar@yahoo.com.

**Editor’s Note: If you find the story here of value, consider clicking one of the Google ads embedded in the story. It costs you nothing but Google will give the website owner a few cents. This is a way to help support local news at no cost to the reader.